AC and TRAN tutorial¶

While the simulation below might me done from the command line with an netlist file, interacting with the simulator inside a Python program gives the user the ability to employ all the extreme flexibility and power of the Python language.

This page gives an beginners tutorial showing how, especially illustrating AC

and TRAN simulations. Please refer to the doc pages for ahkab and

ahkab.circuit for more.

Tutorial¶

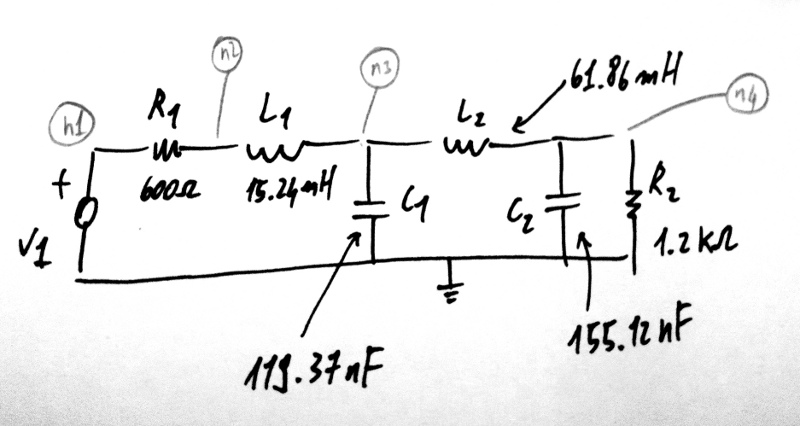

Let’s say we would like to simulate the AC characteristics and the step response of a Butterworth low pass filter, such as this:

This example is example 7.4 in from Hercules G. Dimopoulos, Analog Electronic Filters: Theory, Design and Synthesis, Springer.

The code to describe the circuit is the following:

First import the modules and create a new circuit:

import ahkab

from ahkab import circuit, printing, time_functions

mycircuit = circuit.Circuit(title="Butterworth Example circuit")

Elements are to be connected to nodes. There is one special node, the reference (gnd):

import ahkab

from ahkab import circuit, printing, time_functions

mycircuit = circuit.Circuit(title="Butterworth Example circuit")

gnd = mycircuit.get_ground_node()

and ordinary nodes.

Ordinary nodes can be defined as:

# setup

import ahkab

from ahkab import circuit, printing, time_functions

mycircuit = circuit.Circuit(title="Butterworth Example circuit")

# now we can define the nodes

# 1. using arbitrary strings to describe the nodes

# eg:

n1 = 'n1'

# 2. using the alternative syntax:

n1 = mycircuit.create_node('n1')

# the helper function create_node() will check that this is not a

# node name that was used somewhere else in your circuit

Then you can use the nodes you have defined to add your elements to the circuit. The circuit instance provides convenient helper functions.

The passives in example 7.4 can be added as:

import ahkab

from ahkab import circuit, printing, time_functions

mycircuit = circuit.Circuit(title="Butterworth Example circuit")

gnd = mycircuit.get_ground_node()

mycircuit.add_resistor("R1", n1="n1", n2="n2", value=600)

mycircuit.add_inductor("L1", n1="n2", n2="n3", value=15.24e-3)

mycircuit.add_capacitor("C1", n1="n3", n2=gnd, value=119.37e-9)

mycircuit.add_inductor("L2", n1="n3", n2="n4", value=61.86e-3)

mycircuit.add_capacitor("C2", n1="n4", n2=gnd, value=155.12e-9)

mycircuit.add_resistor("R2", n1="n4", n2=gnd, value=1.2e3)

Next, we want to add the voltage source V1.

- First, we define a pulse function to provide the time-variable characteristics of V1, to be used in the transient simulation:

voltage_step = time_functions.pulse(v1=0, v2=1, td=500e-9, tr=1e-12, pw=1, tf=1e-12, per=2)

- Then we add a voltage source named V1 to the circuit, with the time-function we have just built:

mycircuit.add_vsource("V1", n1="n1", n2=gnd, dc_value=5, ac_value=1, function=voltage_step)

Putting all together:

voltage_step = time_functions.pulse(v1=0, v2=1, td=500e-9, tr=1e-12, pw=1, tf=1e-12, per=2)

mycircuit.add_vsource("V1", n1="n1", n2=gnd, dc_value=5, ac_value=1, function=voltage_step)

We can now check that the circuit is defined as we intended, generating a netlist.

print mycircuit

If you invoke python now, you should get an output like this:

* TITLE: Butterworth Example circuit

R1 n1 n2 600

L1 n2 n3 0.01524

C1 n3 0 1.1937e-07

L2 n3 n4 0.06186

C2 n4 0 1.5512e-07

R2 n4 0 1200.0

V1 n1 0 type=vdc vdc=5 vac=1 arg=0 type=pulse v1=0 v2=1 td=5e-07 per=2 tr=1e-12 tf=1e-12 pw=1

Next, we need to define the analyses to be carried out:

op_analysis = ahkab.new_op()

ac_analysis = ahkab.new_ac(start=1e3, stop=1e5, points=100)

tran_analysis = ahkab.new_tran(tstart=0, tstop=1.2e-3, tstep=1e-6, x0=None)

Next, we run the simulation:

r = ahkab.run(mycircuit, an_list=[op_analysis, ac_analysis, tran_analysis])

Save the script to a file and start python in interactive model with:

python -i script.py

All results were saved in a variable ‘r’. Let’s take a look at the OP results:

>>> r

`{'ac': <results.ac_solution instance at 0xb57e4ec>,

'op': <results.op_solution instance at 0xb57e4cc>,

'tran': <results.tran_solution instance at 0xb57e4fc>}`

>>> r['op'].results

{'VN4': 3.3333333333333335, 'VN3': 3.3333333333333335, 'VN2': 3.3333333333333335,

'I(L1)': 0.0027777777777777779, 'I(V1)': -0.0027777777777777779, 'I(L2)': 0.0027777777777777779, 'VN1': 5.0}

You can get all the available variables calling the keys() method:

>>> r['op'].keys()

['VN1', 'VN2', 'VN3', 'VN4', 'I(L1)', 'I(L2)', 'I(V1)']

>>> r['op']['VN4']

3.3333333333333335

Then you can access the data through the dictionary interface, eg:

>>> "The DC output voltage is %s %s" % (r['op']['VN4'] , r['op'].units['VN4'])

'The DC output voltage is 3.33333333333 V'

A similar interface is available for the AC simulation results:

>>> print(r['ac'])

<AC simulation results for Butterworth Example circuit (netlist None).

LOG sweep, from 1000 Hz to 100000 Hz, 100 points. Run on 2011-12-19 17:24:29>

>>> r['ac'].keys()

['#w', '|Vn1|', 'arg(Vn1)', '|Vn2|', 'arg(Vn2)', '|Vn3|', 'arg(Vn3)', '|Vn4|',

'arg(Vn4)', '|I(L1)|', 'arg(I(L1))', '|I(L2)|', 'arg(I(L2))', '|I(V1)|', 'arg(I(V1))']

And a similar approach can be used to access the TRAN data set.

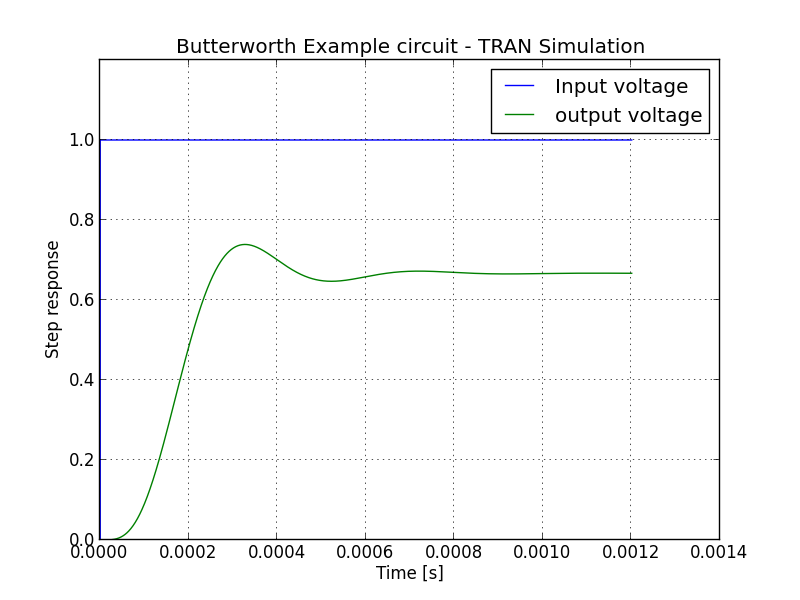

The data can be plotted through matplotlib, for example:

import pylab as plt

import numpy as np

fig = plt.figure()

plt.title(mycircuit.title + " - TRAN Simulation")

plt.plot(r['tran']['T'], r['tran']['VN1'], label="Input voltage")

plt.hold(True)

plt.plot(r['tran']['T'], r['tran']['VN4'], label="output voltage")

plt.legend()

plt.hold(False)

plt.grid(True)

plt.ylim([0,1.2])

plt.ylabel('Step response')

plt.xlabel('Time [s]')

fig.savefig('tran_plot.png')

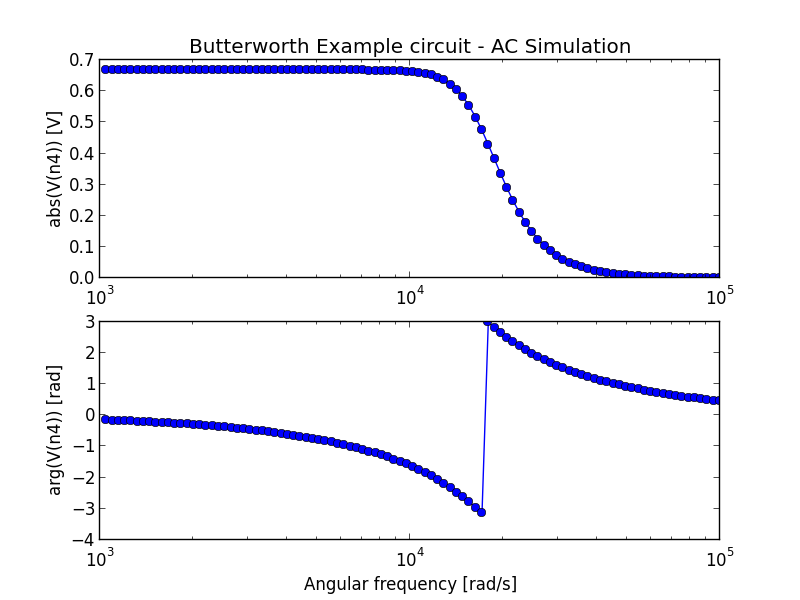

fig = plt.figure()

plt.subplot(211)

plt.semilogx(r['ac']['w'], np.abs(r['ac']['Vn4']), 'o-')

plt.ylabel('abs(V(n4)) [V]')

plt.title(mycircuit.title + " - AC Simulation")

plt.subplot(212)

plt.grid(True)

plt.semilogx(r['ac']['w'], np.angle(r['ac']['Vn4']), 'o-')

plt.xlabel('Angular frequency [rad/s]')

plt.ylabel('arg(V(n4)) [rad]')

fig.savefig('ac_plot.png')

plt.show()

The previous code generates the following plots:

It is also possible to extract attenuation in pass-band (0-2kHz) and stop-band (6.5kHz and up).

The problem is that the voltages/currents we are looking for may not have been evaluated by ahkab at the desired points. This can be easily overcome with interpolation through scipy.

Here is a snippet of code to evaluate the attenuation is pass-band and stop band in the example:

import numpy as np

import scipy, scipy.interpolate

# Normalize the output to the low frequency value and convert to array

norm_out = np.abs(r['ac']['Vn4'])/np.abs(r['ac']['Vn4']).max()

# Convert to dB

norm_out_db = 20*np.log10(norm_out)

# Convert angular frequencies to Hz and convert matrix to array

frequencies = r['ac']['w']/2/np.pi

# call scipy to interpolate

norm_out_db_interpolated = scipy.interpolate.interp1d(frequencies, norm_out_db)

print "Maximum attenuation in the pass band (0-%g Hz) is %g dB" % \

(2e3, -1.0*norm_out_db_interpolated(2e3))

print "Minimum attenuation in the stop band (%g Hz - Inf) is %g dB" % \

(6.5e3, -1.0*norm_out_db_interpolated(6.5e3))

You should see the following output:

Maximum attenuation in the pass band (0-2000 Hz) is 0.351373 dB

Minimum attenuation in the stop band (6500 Hz - Inf) is 30.2088 dB